Citizen Oversight Board

2022 Annual Report

Table of Contents

- Letter from the Board Chair

- Introduction

- Board Mission

- Overview of Denver’s Law Enforcement Discipline System

- Board Activities in 2022

- Board Meetings and Public Forums

- PID Policy Implementation

- Hiring an Independent Monitor

- Other Board Activities

- Notable City Events

- Evaluation of OIM

- Workload and Performance Data

- OIM Staff Survey

- Public Safety Feedback

- Board Assessment

- Assessment of DOS Disciplinary Processes

- Community Concerns

- Board Concerns

- Recommendations

- 2022 Recommendations

- Status of Prior Recommendations

- Appendix A: Strategic Plan Overview

- Appendix B: Board Membership

- Appendix C: Contact Information

Letter from the Board Chair

Greetings,

I welcome you to the Denver Citizen Oversight Board’s annual report for 2022, and I’m proud to highlight a few of the things we’ve accomplished. In February, the Board exercised its newfound authority to select the next Independent Monitor by deciding not to hire any candidate from the first round of recruiting. We then coordinated a new search and selection process, as well as updating the position’s job description and pay grade. After extensive community involvement and partnership, we selected local defense attorney Lisabeth Pérez Castle for the position. We’re thrilled to have her lead the Office of the Independent Monitor and eager to partner with her moving forward.

In addition, the Board engaged in a strategic planning effort and identified a number of objectives for the next two years focused on three strategic areas: 1) Adequate Funding and Operational Resources; 2) Sustained Stakeholder Support: Community Outreach and Involvement; and 3) Unfettered Access to Records and Facilities; Public Reporting and Transparency. We’ve already made progress on several of our objectives, and I’m confident that our progress will accelerate as the new year gets underway.

Core to our mission, we’ve also been paying close attention to the Department of Public Safety. Sadly, 2022 was marked with several human tragedies in Denver and beyond. This report highlights a number of concerns stemming from these and other incidents. As a Board, we are dedicated to ensuring that each of these events leads to lasting and meaningful change.

But there has also been progress, particularly in the form of significant investments in support-oriented services across almost every facet of public safety. A few examples you may not have heard about include that the:

- Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) program was dramatically expanded;

- Co-responder program, which pairs mental health professionals with law enforcement officers, continued to grow both within the Police Department and in other public safety agencies like the Fire Department and Park Rangers;

- Department of Public Safety opened a new Assessment-Intake-Diversion Center where certain low-level offenders can now avoid arrest and instead get immediately connected with available services in a supportive environment, should they want to; and

- Sheriff Department is working to better support inmates undergoing treatment for opioid misuse with a dedicated housing unit that makes it easier to provide treatment and related services.

Change is not just possible, but happening, even if in small local ways. I hope you find that as encouraging as we do.

Sincerely,

Julia Richman, Chair

Introduction

Denver’s Citizen Oversight Board (COB or Board) was created in 2004 and consists of nine community members who are broadly tasked with assessing the effectiveness of the Denver Department of Public Safety’s (DOS) hiring, training, and disciplinary processes and making recommendations as appropriate. In order to do so, the Board is granted regular access to public safety department leaders as well as confidential records. The Board is also responsible for appointing, by and with the consent of the City Council, the Independent Monitor, who shall serve at the pleasure of the Board. The Independent Monitor leads the Office of the Independent Monitor (OIM), the overall performance of which the Board is also responsible for evaluating. Board members serve four-year terms and are appointed alternately by the Mayor and City Council, with one joint appointee. They also receive a stipend of $100 per month. By ordinance, the Board is required to annually report on its activities, findings, and recommendations. This annual report covers the period from January 1 through December 31, 2022.

Board Mission

The duties and authorities of the COB are established in of the City and County of Denver Charter, as follows:

Denver Charter § 12.1.1

(B) The citizen oversight board. There is hereby created the citizen oversight board, the size, qualifications, composition and appointment of which shall be as provided by ordinance. The functions of the board shall be to:

- Assess the effectiveness of the monitor’s office;

- Make policy-level recommendations regarding discipline, use of force, and other policies; rules; hiring; training; community relations; and the complaint process;

- Address any other issues of concern to the community, members of the board, the monitor, the manager of safety, the chief of police, the sheriff, or the fire chief;

- Make recommendations as to specific cases as may be prescribed in ordinance;

- Exercise such other powers and duties as may be provided by ordinance; and

- In addition to executing the powers and duties assigned to the citizen oversight board, the citizen oversight board shall appoint, by and with the consent of city council, the monitor or any appointee who will serve as monitor in the interim. The monitor shall serve at the pleasure of the citizen oversight board.

Both the Board and the OIM were created in 2004. Over the past few years, the Board and its responsibilities have been modified in significant ways.

In February 2019, the City Council unanimously passed bill 19-0029, which expanded the Board from seven members to nine, staggered the terms of its members, and split appointment authority evenly between the Mayor and City Council. (Previously, the Mayor was responsible for all appointments.)

That ordinance also strengthened the authority of the OIM. It explicitly confirmed the OIM’s ability to oversee investigations of Denver’s Sheriff or Chief of Police, its ability to review settlements and anyother method of closing discipline cases, and its ability to publish as many reports as it sees fit. It also prohibited retaliation against anyone who reported to or worked with the OIM.

In November 2021, 70.25% of Denver voters approved Referred Question 2G, which amended Denver’s Charter in order to give the Board the authority to appoint the Independent Monitor with the consent of the City Council. It also gave employment protections to OIM employees. Finally, it allowed the OIM to hire their own outside legal counsel if necessary.

Complaints and Commendations

The COB can receive complaints against, and commendations of, uniformed law enforcement officers. Complaints and commendations may be submitted by email, mail, over the phone, or through the OIM’s online complaint and commendation form. Complaints and commendations received by the COB are forwarded to the OIM, which then refers them to the relevant agency and then monitors how they handle them. The COB has no investigative authority.

Overview of Denver’s Law Enforcement Discipline System

The DOS is headed by the Executive Director of Public Safety (EDOS) and staffed with civilians. The EDOS is a Mayoral appointee and is responsible for, among other things, managing the Denver Fire Department (DFD), Denver Police Department (DPD), Denver Sheriff Department (DSD), and the 911 Emergency Communications Division. The Mayor also appoints the heads of the DFD, DPD, and DSD.

Public safety employees fall into one of two groups: civilian employees and those with badges and guns, who are sometimes called sworn, uniformed, or classified service employees. The approximately 1,600 police officers, 875 sheriff deputies, and 15 fire investigators with badges and guns will be collectively described in this annual report as “uniformed personnel.”

Complaints

Any member of the community can file a complaint against any uniformed personnel that they believe may have acted improperly. Complaints can be filed anonymously and can be made by anyone, including witnesses or those who heard about an incident from someone else. Complaint topics can include disrespectful treatment, improper use of force, or any other allegation against specific uniformed personnel, regardless of whether the complainant knows their name(s) or badge number(s). Complaints can be provided to the COB, the OIM, or directly to the applicable department’s internal investigative office. The easiest way to file a complaint or commendation related to the DPD or DSD is through the OIM’s online form.1 The DFD has an online form available as well.2

Historically, both DPD and DSD had their own internal affairs offices that were responsible for investigating allegations of misconduct concerning uniformed personnel and recommending appropriate discipline. This is still the case for the DPD, which has both an Internal Affairs Bureau (IAB) responsible for initial screening of complaints, gathering evidence, and conducting interviews and a Conduct Review

Bureau (CRB, often also referred to as the Conduct Review Office or CRO) responsible for evaluating the evidence and making initial disciplinary recommendations. However, the DSD’s internal affairs division was replaced in 2019 by a Public Integrity Division (PID) within the DOS. The PID consists of an Administrative Investigations Unit (AIU) and a Conduct Review Unit (CRU), which have responsibilities similar to their DPD counterparts. While complaints can be made through many channels, complaints about DSD uniformed personnel go first to AIU, then CRU, and then to the Sheriff. Complaints about DPD uniformed personnel go first to IAB, then CRB, and then to the Chief of Police. While reprimands can be issued by the Chief of Police, Sheriff, or EDOS, the EDOS is responsible for the final decision on any discipline for uniformed personnel more severe than a reprimand.3 This process is the same regardless of whether a complaint is initially submitted to the Board, the OIM, the DSD’s Grievance and Incident Review Team (GIRT), or directly to AIU or IAB.4

After the EDOS makes the department’s final discipline decision, police officers and fire investigators are able to appeal that decision to the Civil Service Commission. Sheriff deputies and most civilian employees can similarly appeal to the Career Service Board. They can further appeal their decisions through the court system as well if they believe their discipline violated state or federal laws.

Oversight

The OIM and the COB were created in 2004 in order to increase public trust in the internal misconduct investigations of uniformed personnel. Their creation was part of the reforms that were demanded in the wake of the fatal 2003 police shooting of Paul Childs, a developmentally disabled teenager. They replaced the Public Safety Review Commission, which was perceived to be ineffective.

The OIM is responsible for monitoring all aspects of the investigatory and disciplinary process for uniformed personnel and typically does so by reviewing records and making recommendations after each stage of the process is completed. This includes reviewing cases that the law enforcement review units wish to close after an initial screening. If the OIM so chooses, they can also “actively monitor” a case. When the OIM actively monitors a case, its staff works closely with the investigators—including attending relevant interviews—and can provide feedback and recommendations in real-time. If the investigating unit declines the OIM’s recommendations, the OIM has the authority to conduct its own supplemental investigation. The OIM is also tasked with reporting on overall trends in complaints and discipline, which can inform policy recommendations.

The goal of this oversight system is for Denver residents to have faith that their complaints will be handled properly, that the resulting investigation will be thorough, and that those in charge will hear an independent perspective before they make any disciplinary decisions.

The Board is not directly involved in each step of the investigatory and disciplinary process like the OIM, but is able to review confidential records and provide recommendations for both specific cases and general policies as it sees fit. The Board is also tasked with appointing the head of the OIM (with the consent of the City Council) and independently evaluating the effectiveness of the office.

Board Activities in 2022

Board Activities 2022

Board Meetings and Public Forums

City ordinance requires that the Board meet with the Independent Monitor at least bi-monthly, meet with the EDOS, the Sheriff, and the Chief of Police at least once each quarter, and meet for public comment at least three times each year. The Board met each of these requirements in 2022.

Almost all of the Board’s meetings in 2022 were virtual. In 2022, the Board held 17 regular meetings, 3 strategic planning meetings, and 3 public forums (March 23, May 24, and August 23). Channel 8 broadcasted each of the public forums and maintains a publicly accessible archive of past forums. In addition, the Board hosted 4 virtual community forums featuring finalists for the Independent Monitor position (February 16, February 17, November 29, November 30).

Board Meeting Times

The Board also met several times in non-public settings in order to interview candidates for the position of Independent Monitor (January 27, January 28, and November 18) and to visit the Downtown Detention Center (May 6).

Board Working Sessions

The Board regularly meets for working sessions at 10 a.m. on the first and third Fridays of each month. These meetings are open to the public, with the exception of executive sessions held to discuss ongoing investigations and other privileged matters. The Board works closely with the OIM to stay informed about noteworthy misconduct cases, and an OIM representative attends most Board meetings.

In September, the Board was also excited to participate as a table host in Servicios de la Raza’s 50th Anniversary Fiesta Cookout at Chaffee Park. The Board looks forward to participating in more community events in 2023.

PID Policy Implementation

In 2021 Annual Report

In its 2021 annual report, the Board recommended that the DOS promptly implement formal operating policies for its Public Integrity Division (PID) and then review and refine them on a regular basis. Although it began operating in 2019, neither the AIU nor CRU had official published policies governing their operations.

After the Board issued its 2021 annual report, the Board met with EDOS Armando Saldate and representatives from the DOS, City Attorney’s Office, and OIM to identify the necessary remaining steps and set a schedule to finalize the policies.

The Board was thereafter provided with the opportunity to review the current drafts of the policies, and for the second time (the first being in October 2021) provided detailed suggestions for changes that it believed would significantly improve the clarity of the policies. The DOS incorporated most of the Board’s suggested changes.

Restructuring the Board

On June 3, 2022, EDOS Saldate informed the Board that he would be restructuring the PID by eliminating the position of PID Director (a Mayoral appointee) and having the leaders of both the AIU and CRU, which had previously reported to the PID Director, report directly to the Chief Deputy Executive Director of DOS.

On June 27, EDOS Saldate signed into effect formal policies and procedures for the AIU and CRU. Notably, as EDOS Saldate had committed to in December 2021, these policies require that AIU record all complaints they receive in the IAPro database rather than on ad hoc spreadsheets. This enhanced tracking system will make it easier to ensure that the OIM is able to review each complaint prior to its closure and reduce the risk of complaints being lost or overlooked.

Hiring an Independent Monitor

Throughout 2022, the Board dedicated a significant amount of time and energy towards this responsibility.

Throughout 2022, the Board dedicated a significant amount of time and energy towards this responsibility. In January 2022, the Board interviewed the three finalists for the Independent Monitor position forwarded to the Board by the Screening Committee. On February 16 & 17, the Board partnered with several local community organizations to co-host virtual events where the community could engage with the candidates. On March 1, 2022, the Board announced that it declined to hire any of the three finalists selected by the original Screening Committee and would continue the search for an Independent Monitor. Though each candidate had admirable experience and qualifications, the Board felt that none were quite the right fit for Denver’s particular challenges and opportunities.

Immediately thereafter, the Board solicited proposals from search firms to assist in recruiting candidates for the Independent Monitor position, evaluated those proposals, and selected a vendor for this engagement. In April and May, the Board worked to create a new Screening Committee and coordinated with the City Attorney’s Office to negotiate contract language with the recruiting firm and navigate the City’s contract approval process.

Immediately thereafter, the Board solicited proposals from search firms to assist in recruiting candidates for the Independent Monitor position, evaluated those proposals, and selected a vendor for this engagement. In April and May, the Board worked to create a new Screening Committee and coordinated with the City Attorney’s Office to negotiate contract language with the recruiting firm and navigate the City’s contract approval process.In June, Board began working with the recruiting firm to conduct stakeholder meetings. In July, the Board updated the job description for the Independent Monitor position and drafted a recruitment brochure for the position. Active recruiting efforts took place in August and September, with the Screening Committee conducting interviews in October and moving two candidates forward to the Board at the end of the month. During that time, the Board also requested that a pay study be conducted for the Independent Monitor’s position, which the City’s Office of Human Resources (OHR) conducted. As a result, the pay grade for the position of Independent Monitor was increased one level from EX-16 to EX-17.

The Board conducted their interviews of the two finalists in November and organized a community process as required by ordinance. That community process consisted of 5 meetings with stakeholders including public safety leadership, public safety union representatives, the interim monitor, and two virtual forums open to the public that were co-hosted with local community groups. All participants were given the opportunity to provide their feedback, and the Board reviewed all available input prior to making their unanimous selection of Lisabeth Pérez Castle on December 3 to be the next Independent Monitor. The remainder of the year included coordination with OHR and City Council to formalize Ms. Castle’s offer and then appointment.

Other Board Activities

Strategic Planning

During the summer of 2022, the Board hired a consultant to help guide the Board through the process of creating a strategic plan. The Board met three times to discuss their values, evaluate possible priorities, formalize decision-making processes, set goals, and assign leaders to each goal. At the conclusion of the strategic planning process, the Board identified three strategic goals, each with underlying objectives and activities. The strategic goals are: 1) Adequate Funding and Operational Resources; 2) Sustained Stakeholder Support: Community Outreach and Involvement; and 3) Unfettered Access to Records and Facilities; Public Reporting and Transparency. A more detailed summary of the plan can be found in Appendix A.

2023 Budget

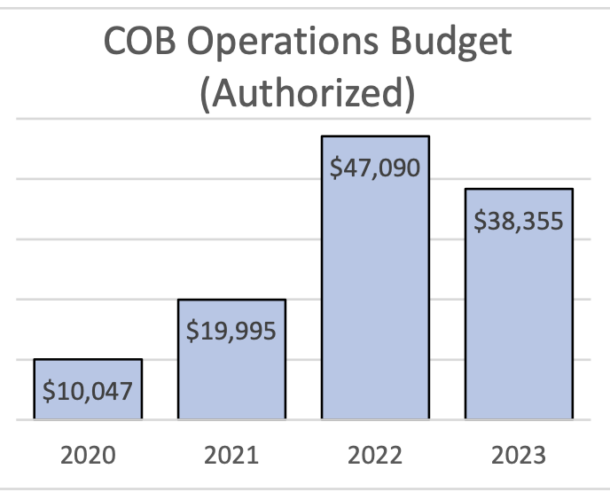

The Board did not request a budget expansion for 2023. With the expiration of $8,735 in one-time funding, the Board’s 2023 budget has declined to $38,355.6

In 2022, the Board also received its own cost center for personnel costs, allowing for more precise tracking of its personnel budget moving forward.

Public Engagement and Communications

In September 2022, the Board created a web page entitled “Oversight in Denver.” 7 The page is intended to serve as a central hub for community members interested in learning more about Denver’s law enforcement accountability systems. In addition to a written overview, it includes links to a wide variety of public safety information and records, and also features a list of documents and media reports that provide significant historical perspectives on the work of the Board and OIM.

Conference Attendance

On September 11-15, 2022, Board member Larry Martinez and Board Administrator Daniel Van Schooten traveled to Fort Worth, Texas, to attend the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement’s (NACOLE) annual conference. The conference provides an opportunity to connect with and learn from civilian oversight practitioners around the country. The conference featured two programming tracks with sessions focused on national best practices in civilian oversight, prison and jail oversight, strengthening oversight institutions, legal issues, and more.

Notable City Events

Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) program experienced significant growth throughout 2022.8 On February 14, City Council unanimously approved a $1.4 million contract to continue and significantly expand the STAR program over the course of the year.9 With additional funds from Caring for Denver, this gave the program an annual operating budget of $3.9 million.10 In June, an academic paper was published finding that the STAR program reduced reports of low-level offenses by 34% in the areas it was active, in addition to being very cost-effective.11 Also in June, the City Council approved an additional $526,610 to purchase 5 new vans for the program.12 In October, the City approved a $2.3 million contract with Servicios de la Raza to provide a local network of wrap-around services as a new part of the STAR program.13 A $2.5 million contract for 2023 was introduced in November 2022, pointing to the program’s continued growth in 2023.14

On March 25, a federal jury ordered the City and County of Denver to pay $14 million to 12 plaintiffs as a result of the DPD’s actions during the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020. The jury found that the plaintiff’s First and Fourth Amendment rights had been violated as a result of the DPD’s policies and practices. In 2022, City Council also approved five settlements related to the DPD’s conduct during the George Floyd protests at a cost of $1.75 million. An additional $1.75 million was spent settling 15 other settlements related to the DPD. City Council also approved two settlements worth $290,000 related to the conduct of the DSD.

On May 9, the DSD dedicated one of its housing pods specifically to inmates who are participating in the Department’s pre-existing Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) program. Participation in the program, which is aimed at combating opioid addiction, is voluntary and the pod has capacity to house approximately 60 inmates. As a result, 578 inmates participated in the MAT program in 2022, more than twice as many as 2021.

On July 17, during the early morning “out crowd” that occurs when Lower Downtown (LoDo) bars close, three DPD officers fired at Jordan Waddy, injuring him and six other bystanders near the intersection of 20th and Larimer Streets. The Board issued a public statement on August 9, in which it committed to “take every step in our power to ensure that the investigative process is worthy of the community’s trust” and communicate about the process and seek to improve any deficiencies it found. The body camera and related other footage was released on August 16. Neither the OIM nor the COB had independent or direct access to the relevant video files prior to the footage’s public release.16 This limited the Board’s ability to serve as an independent and trustworthy voice to the community. That day, Denver District Attorney Beth McCann announced that she was convening a grand jury to investigate the incident.17 Once the criminal proceedings are completed, the DPD will conduct an administrative review to determine if any policies were violated and if disciplinary actions are warranted.

On August 31, DPD Chief Paul Pazen announced his retirement, and the Mayor appointed Division Chief of Patrol Ron Thomas to serve as Acting Chief. Thomas’s appointment as Chief was confirmed by City Council on October 18.

On March 25, a federal jury ordered the City and County of Denver to pay $14 million to 12 plaintiffs as a result of the DPD’s actions during the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020. The jury found that the plaintiff’s First and Fourth Amendment rights had been violated as a result of the DPD’s policies and practices. In 2022, City Council also approved five settlements related to the DPD’s conduct during the George Floyd protests at a cost of $1.75 million. An additional $1.75 million was spent settling 15 other settlements related to the DPD. City Council also approved two settlements worth $290,000 related to the conduct of the DSD.

On May 9, the DSD dedicated one of its housing pods specifically to inmates who are participating in the Department’s pre-existing Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) program. Participation in the program, which is aimed at combating opioid addiction, is voluntary and the pod has capacity to house approximately 60 inmates. As a result, 578 inmates participated in the MAT program in 2022, more than twice as many as 2021.

On July 17, during the early morning “out crowd” that occurs when Lower Downtown (LoDo) bars close, three DPD officers fired at Jordan Waddy, injuring him and six other bystanders near the intersection of 20th and Larimer Streets. The Board issued a public statement on August 9, in which it committed to “take every step in our power to ensure that the investigative process is worthy of the community’s trust” and communicate about the process and seek to improve any deficiencies it found. The body camera and related other footage was released on August 16. Neither the OIM nor the COB had independent or direct access to the relevant video files prior to the footage’s public release.16 This limited the Board’s ability to serve as an independent and trustworthy voice to the community. That day, Denver District Attorney Beth McCann announced that she was convening a grand jury to investigate the incident.17 Once the criminal proceedings are completed, the DPD will conduct an administrative review to determine if any policies were violated and if disciplinary actions are warranted.

On August 31, DPD Chief Paul Pazen announced his retirement, and the Mayor appointed Division Chief of Patrol Ron Thomas to serve as Acting Chief. Thomas’s appointment as Chief was confirmed by City Council on October 18.

On September 12, City Council approved an amendment to the City’s contract with WellPower (formerly Mental Health Center of Denver) to provide three mental health clinicians who will participate in a co- responder program with the Fire Department and Park Rangers.18

On November 8, Fire Chief Desmond Fulton revised several policies related to discipline for DFD employees. These policy revisions formalized several pre-existing practices, including referring misconduct allegations against DFD leadership and DFD Internal Affairs personnel to the Public Integrity Division for an independent investigation, completing misconduct investigations even if the subject employee resigns, and promptly notifying the OIM in cases where they have jurisdiction.

On November 14, City Council approved the City’s budget for 2023. Numerous changes were related to public safety, but two specific changes are highlighted here:

- The budget re-allocates funds for the DFD to move Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) training in-house instead of relying on Denver Health. Relatedly, the City’s 2023 contract with Denver Health also allows trained DFD first responders to immediately provide advanced life support services, such as administering intra-veinous medications, rather than waiting for Denver Health personnel to arrive.

- The budget funds the creation of a new “public health hot spot” program, which will “provide a proactive, multi-agency approach to addressing mental, health and social issues” in specific areas with a higher concentrations of public health needs. The team will consist of two outreach coordinators, two emergency medical technicians, and three therapists.

On November 21, the DOS soft-launched their new Assessment-Intake-Diversion (AID) Center and began serving community members in need of services.19 Logistical and programmatic work on the AID Center continued into 2023.

On December 16, EDOS Saldate informed the Board that a policy requiring the DPD to promptly share footage of critical incidents with the OIM and the Board was in the final stages of legal review. This policy change was requested by the Board after the July 17 officer involved shooting in LoDo.

Also on December 16, EDOS Saldate informed the Board that he will be initiating a formal process to review the feasibility of changing body worn camera settings so that they include audio in the 30-second buffer recording prior to the camera’s activation. This commitment comes after the Board asked EDOS Saldate, Chief Thomas, and former Chief Pazen a variety of questions related to this subject over the course of the year.20

Evaluation of OIM

The COB uses a four-pronged approach to evaluate the OIM:

1. A series of quantitative workload and performance measures

2. An anonymous survey of OIM staff

3. Feedback from DOS leaders

4. An assessment from COB members on several specific OIM responsibilities

Senior Deputy Monitor Gregg Crittenden served as interim Independent Monitor for the entirety of 2022.

Workload and Performance Data

Across the board, the OIM’s complaint-driven workload increased significantly in 2022, with a particularly large 72% increase in complaints against the DSD and corresponding increases in the number of investigations reviewed and actively monitored. The OIM’s outreach activities also increased significantly, although they still remain less than pre-pandemic levels.

Mediations of complaints decreased from what were already pandemic lows. However, the OIM has no direct control over the number of mediations that occur. All of the involved parties must agree to mediation.

The OIM provides more details about each critical incident (officer involved shootings and deaths in custody or during law enforcement contact) in their annual and semi-annual reports.

Table 1: OIM Workload Measures, 2019 – 202222

| 2022 Workload DataComplaint Workload | Police | Sheriff | 2022 Total | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Misconduct Complaints (Community + Internal) | 398 | 409 | 807 | 656 | 804 | 788 |

| Investigations Reviewed | 360 | 389 | 749 | 627 | 716 | 848 |

| Actively Monitored Investigations | 35 | 65 | 100 | 58 | 110 | 179 |

| Disciplinary Cases Reviewed | 124 | 130 | 254 | 217 | 245 | 283 |

| Disciplinary Cases Reviewed | 12 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 38 |

| Critical Incident Workload | ||||||

| Officer Involved Shootings | 8 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 |

| In-Custody & In-Contact Deaths | 6 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

Table 2: OIM Performance Measures, 2019 – 202223

| Performance Indicator Category | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Percentage of DPD IAB Investigations (full formal investigations and declines) reviewed by OIM prior to case closure | 100% | 96% | 97% | 100%* |

| 2. Percentage of DOS AIU Investigations (full formal investigations and declines) reviewed by OIM prior to case closure | 99% | |||

| 3. Percentage of DPD disciplinary decisions reviewed by the OIM prior to case closure | 100% | 93% | 95% | 91% |

| 4. Percentage of DSD disciplinary decisions reviewed by the OIM prior to case closure | 100% | |||

| 5. Number of community outreach events held/attended by the OIM in a calendar year | 138 | 65 | 62 | 182 |

| 6. Number of officer/deputy outreach events held/attended by the OIM in a calendar year | 35 | 26 | 19 | 78 |

| 7. Number of complaint/commendation form distribution sites | 81 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 8. Percentage of community complaints referred to DPD IAB within three business days (for complaints filed through the OIM) | 98% | 99% | 95% | 97% |

| 9. Percentage of community complaints referred to DOS AIU within three business days (for complaints filed through the OIM) | 97% | |||

| 10. Percentage of community complaints against DPD mediated | 5% | 7% | 4% | 9% |

Public Safety Feedback

The Board provided the Sheriff, Chief of Police, and EDOS with the opportunity to share their feedback on the OIM’s performance in 2022. Only Chief Thomas provided feedback, stating that “the office operated as expected and generally in accordance with their mandate.” As a potential area of improvement, he also shared that OIM’s response times were sometimes slower than preferred.

Board Assessment

Board members were asked to evaluate the Interim Independent Monitor’s performance across ten key areas. The following entries reflect the consensus of the Board.

1. Communication with the COB:

Given the complexity, size, and scope of the issues the OIM oversees, the Interim Independent Monitor did an excellent job of keeping the Board apprised of significant incidents, investigations, and disciplinary issues. The OIM promptly responded to Board requests for data, briefings, or meetings, and provided updates on emerging issues, helping the Board avoid surprises and understand the context of the OIM’s work.

2. Monitoring of Investigations:

The OIM provided thorough and well executed oversight of misconduct investigations, providing recommendations for additional work when appropriate. As highlighted above in Table 1, the number of complaints increased significantly in 2022 as the pandemic subsided and officer contacts increased. The OIM continues to manage a heavy investigation workload with success.

3. Monitoring of Discipline:

The OIM is willing to make recommendations that differ from those of the DPD, DSD, or DOS. They also do a commendable job of expressing and following up on those recommendations which enables them to ensure, where possible, that appropriate actions are taken while maintaining professional relationships with their counterparts.

4. Monitoring Critical Incidents:

An OIM staff member is always on call to respond to critical incidents, and once notified, the office responds appropriately. Previous concerns about the OIM not being properly notified when a critical incident occurs appear to have been resolved in 2022.

5. Production of Reports:

The OIM published its annual and semi-annual reports as required. However, the Board feels that there is an opportunity for the OIM to increase communication with the public about their policy work and the sufficiency of misconduct investigations conducted by DPD, DSD, or DOS and the appropriateness of their disciplinary actions.

6. Production of Policy, Practice, and Training Recommendations:

In addition to recommendations in its published reports, the OIM regularly makes policy, practice, and training recommendations directly to the DPD, DSD, and DOS.

7. Outreach to complaint process stakeholders:

As highlighted above in Table 2, the OIM significantly increased its outreach activities in 2022, although they still remain short of pre-pandemic levels. The hiring of a new Independent Monitor presents a great opportunity to enhance the public’s awareness of the work performed by OIM and results of investigations. There can never be too much community engagement and communication from OIM.

8. Oversee Mediation program:

As highlighted above in Table 1, mediations of complaints decreased from what were already pandemic lows. While the OIM is unable to control the number of cases that proceed to mediation, the Board feels it is important that OIM commit to working with contracted mediators and other stakeholders to enhance the mediation program’s visibility and perceived legitimacy.

9. Management of OIM:

As highlighted above, OIM staff gave highly positive responses to a survey seeking their perceptions of the performance of the Office’s leadership and culture. OIM functioned as a team and was well managed under the leadership of the interim Independent Monitor. With the appointment of a new Independent Monitor removing uncertainty about a future leader, the Board anticipates that the OIM will continue to function at a high level. The Board also notes that there have been ongoing issues related to the facilities where OIM is located that affect the OIM’s productivity. The Board offers its full support to the new Independent Monitor as she works with the City to address these deficiencies.

10. Overall:

The Board is grateful to Gregg Crittenden for serving as the interim Independent Monitor for two years, a much longer period of time than originally anticipated. His work and that of the OIM as a whole under his leadership is painstaking, comprehensive, and important for the City. The staff are resilient and take on the challenges and burdens of public safety oversight and reform with diligence and courage.

Assessment of DOS Disciplinary Processes

Community Concerns

While the Board is legally required to maintain the confidentiality of misconduct investigations, community members sometimes share their concerns in public settings and the DOS publicly shares information about some closed cases when they result in significant discipline. This section summarizes notable concerns that members of the community have shared with the Board.

The In-Custody Death of Leroy Taylor

On February 9, 2022, Leroy Taylor died while in the custody of the DSD. Subsequent statements to the media from Taylor’s family, cellmate, and other inmates provided more information to the public. Taylor was diagnosed with COVID-19 on February 1 and taken to the hospital. On February 5, he returned to the Downtown Detention Center after testing negative. Over the next four days, Taylor complained of serious and worsening symptoms, including chest pain, difficulty breathing and swallowing, and that his hands and legs were turning blue. 24 By February 7, his public defender described him as barely audible and claimed in an emergency motion for his release that Denver Health and Hospital Authority (DHHA or Denver Health) had denied his request to remain at the hospital because too many inmates were in need of medical care.25 DSD deputies took Taylor to the medical ward five times in the days before and the day of his death, but Denver Health allegedly did not provide any medical care, and gave him ice chips before sending him back to his cell.26 Over a week after his death, media reports announced that Denver Health had suspended the charge nurse involved, although Denver Health never publicly confirmed the action.27

On March 4, community member Thomas Hernandez publicly shared his concerns with the Board, highlighting additional questions about when and how Taylor was pronounced as deceased and the availability of healthcare to inmates, especially those in COVID-positive housing pods.

Three different investigations were opened following the incident: DPD investigated whether the death was a homicide or otherwise the result of criminal actions, the PID investigated whether any DSD deputies violated departmental policies, and Denver Health investigated the conduct of their employees. DPD and the PID completed and closed their investigations without taking further action. Throughout 2022, the Board asked Sheriff Elias Diggins and EDOS Saldate if they had received or reviewed a copy of Denver Health’s internal investigation. Neither received such a report.28

The events surrounding Taylor’s death are particularly concerning to the Board, as they point to a gap in accountability and oversight concerning medical care provided to inmates. Each year, the City and County of Denver contracts with Denver Health, a state-level public entity, for a wide variety of services, including health care for inmates. The Sheriff is ultimately responsible for conditions in the jails, which and complex undertaking—by contracting with Denver Health.

Inmates who believe they were mistreated by Denver Health staff can and do file complaints. In January 2022, Denver Health informed the Board that it receives, on average, over 150 inmate complaints each month concerning its medical care services.29 Unfortunately, the Board and the OIM have no insight into how those complaints are ultimately handled by Denver Health. The OIM’s case monitoring jurisdiction is limited to uniformed personnel and AIU’s governing policy language similarly does not provide for investigations into the conduct of civilian or contracted staff. As a result, when the AIU receives a complaint related to medical care, they simply forward it to Denver Health and then close the case in their system.

In general, there are disincentives for Denver Health to conduct thorough investigations or be transparent about their investigative findings. Such transparency may create liability risks as well as risks to their contract with the City and reputation with the public. However, this should not outweigh a full and fair assessment of the merits of any complaint against Denver Health’s medical personnel and the disclosure of the results of that assessment.

A media report from early 2022 describes an instance that supports the Board’s concerns about Denver Health’s ability to police itself: In November 2021, a Denver Firefighter witnessed concerning behavior by a paramedic and filed a complaint about it.30 According to the complaint, a Denver Health paramedic encouraged a victim of domestic violence with a head injury to walk to a hospital rather than take an ambulance. The complaint also stated that the paramedic said the hospital was 4 blocks away when in reality it was over a mile—closer to 14 blocks—away. The article quoted DFD Chief Desmond Fulton as saying: “There would never be a plausible reason to tell a person to walk 14 blocks to a hospital.” Nevertheless, Denver Health reportedly cleared their staff of any wrongdoing, and did so without ever talking to the firefighter who complained or the subject paramedic. “I believe in our people and I trust them,” Denver Health Chief Paramedic Gary Bryskiewicz told the media.

While in-custody deaths are uncommon in Denver jails, the COB is concerned that the current level of oversight is not sufficiently transparent for this Board to trust that Denver Health is appropriately handling individual cases of alleged misconduct. In addition, oversight is not just about accountability— assigning blame and then discipline—but also about identifying areas where, even if no misconduct occurred, service can be improved and future tragedies can be avoided.

As it stands, the most effective tool available to inmates who feel they have been mistreated is a private lawsuit. It is, however, unreasonable to assume that inmates have the financial resources to use that tool. Further complicating the situation, an inmate under the care of Denver Health likely has little to no direct access to relevant evidence and cannot easily tell if the medical treatment they received violated policy, given that Denver Health does not publicize any of their policies.

The Board is concerned about the limited information available about how well this partnership between Denver Health and DSD is working. While the Sheriff appears to believe that DSD has sufficient internal mechanisms for accountability and that Denver Health provides quality care to inmates, it does not appear that Denver Health regularly provides the DSD with documentation related to complaint resolution or internal investigations. The Board will seek additional information in 2023 about the mechanisms for accountability, their breadth and effectiveness, as well as data about the frequency, subject matter, and disposition of healthcare complaints. 33

Dispatching and Police Response in the East Colfax Community

Community member Ma Kaing was shot and killed on July 15, 2022, when a group of young men on the other side of the street opened fire on a passing vehicle. DPD arrested four men in August and believe an unidentified fifth suspect may remain at large.

Kaing’s tragic death brought increased attention to how 911 calls are dispatched in the East Colfax community, which borders the city of Aurora. When Kaing’s son dialed 911, the nearest Verizon cell tower was in Aurora, and his call was incorrectly routed to Aurora’s 911 call center. He waited on hold for almost 4 minutes before connecting with Denver’s 911 call center.

In August, Verizon announced that it would begin providing more accurate location-based routing services in Denver and nationwide in early 2023. That technology routes calls to 911 based on a user’s GPS location, rather than the location of the nearest cell tower. Unlike other major carriers, Verizon had reportedly declined a prior request from Denver to implement the technology.

While the call routing issue appears to be in the process of being resolved, community members from the East Colfax community shared three additional concerns with the Board in September. Specifically, they expressed: 1) concerns with how Denver’s 911 call center handles calls in languages other than English or Spanish;36 2) suspicion that Denver 911 dispatchers might be deprioritizing calls in their community, such as reported gunfire, as compared to other communities; and 3) suspicion that DPD has under-resourced their community, resulting in significantly slower or nonexistent police responses compared to similar emergencies in other Denver communities.

The Board looks forward to helping these community members access and review data relevant to their concerns in 2023.

STAR (Support Team Assisted Recovery) Community Advisory Committee

Denver’s STAR program is an alternative-response model in which a van with a paramedic and a mental health specialist is dispatched to certain 911 calls instead of DPD officers. Officers can also request that STAR assume responsibility for calls that they respond to initially. The STAR program is managed by the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment (DDPHE), which works closely with the DOS’s 911 Call Center to implement the program. DDPHE contracts with WellPower (formerly named Mental Health Center of Denver) to provide the necessary mental health professionals and with Denver Health to provide paramedics.

The program started as a pilot in 2020, was made permanent in 2021, and expanded significantly in 2022. In 2021, DDPHE created the STAR Community Advisory Committee (SCAC), which consisted of 15 volunteers, several of whom played a role in the creation of the STAR program. Over the following year DDPHE and the SCAC had different ideas about the purpose of the committee and how much authority, if any, it should have over the program. Tensions rose significantly over the summer of 2022, when a DDPHE staffer unilaterally ended the committee’s monthly virtual meeting after committee members criticized an email sent by the staffer as racist. In their next meeting, DDPHE Executive Director Bob McDonald attended and appeared to take meaningful steps toward reconciliation by re-assigning the staffer and offering additional authority to the committee. However, prior to the committee’s next meeting, DDPHE cancelled all SCAC meetings “for the next couple of months” while they restructure the committee and more clearly define its role.37 In an unofficial public meeting afterwards, SCAC members described a complete breakdown in communications and trust with DDPHE and even suggested advocating that STAR be removed from DDPHE’s management in the future.

The Board is deeply concerned by the breakdown in communications between DDPHE and the SCAC and the potential for that conflict to broadly undermine the community’s trust in the STAR program. The Board will examine this issue more closely in 2023.

Inadequate Investigation of Bicycle Death

On September 5, 2021, community member Gene McCullough died while riding his bike in western Denver. According to a disciplinary order issued in August, the DPD Detective assigned to investigate the death “failed to perform a reasonable investigation,” including not visiting the scene of the death to take pictures until over five weeks later, accompanied by his sergeant.38 In December 2021, the detective, once again accompanied by his sergeant, returned to the scene to take measurements with a laser scanner.

Later in December, after one of McCullough’s relatives filed a complaint about the inadequate investigation, the detective’s second-level manager, a lieutenant, got involved. He emailed both the detective and his sergeant a list of five items needed to complete the investigation. Four months later, the end of April 2022, those five items had still not been completed and added to the report.

The DPD did not find any evidence that McCullough was the victim of a crime, but McCullough’s family is skeptical that a single-person bicycle accident could be fatal for an experienced biker wearing a helmet. The DPD’s failure to conduct a reasonable investigation has done little to reassure them.

After a disciplinary investigation, the detective was fined 2 days of leave for failing to file a proper report.

McCullough’s relative, who filed the initial complaint, believes that the discipline imposed was insufficient, and also shared concerns with the Board about the way the case’s findings were communicated to him. In September 2022, the Board Chair emailed EDOS Saldate and requested that he arrange for someone to call McCullough’s relative and address his concerns about the adequacy of the discipline. The Chair also requested that the DOS work with the OIM to identify and address the reason why neither the DPD nor the DOS notified the complainant of an additional sustained policy violation related to his complaint that resulted in a written reprimand for another officer. 39 Over a month later, the relative told the Board that he never received such a call nor any additional explanation from the DOS, and he later expressed that he no longer has any faith in the DPD or DOS.

The Board sympathizes with the concerns expressed by McCullough’s relative. In any context, it is incredibly frustrating to be dependent on someone who is not doing their job. The intensity of that frustration understandably multiplies when the matter involves the unexpected death of a loved one.

Board Concerns

AIU Complaint Triage Practices

In last year’s annual report, the Board highlighted concerns about the AIU’s use of ad hoc spreadsheets to manage their intake process. Those concerns were subsequently addressed when AIU agreed to use the IAPro database to track all incoming complaints, which began in January 2022, and was formalized in AIU’s policy documents in June 2022.

In those new policies, the AIU is authorized to refer certain complaints back to the DSD for investigation rather than open a formal AIU investigation. To the extent that complaints do not clearly allege deputy misconduct, the Board takes no position on the practice of referring these complaints back to the DSD from the AIU.

However, as EDOS Saldate acknowledged in a December 16, 2022, meeting with the Board, there have been deficiencies in the referral process. For example, it has not always been clear why the AIU refers a case to the DSD for investigation. He mentioned several steps that are being considered to address the issue, but the Board is not aware of any actions or policy changes that took place in 2022 related to the Board’s concerns.

It is the Board’s position that the DSD should not be investigating any complaints of deputy misconduct. First, it is not their job to do so and it has not been since 2019, when the AIU was created and the DSD’s Internal Affairs team was disbanded. Second, the DSD’s uniformed personnel are seriously understaffed and are required to work overtime each week. As such, the AIU should be very hesitant to place any additional burdens on their time. Third, such investigations create potential conflicts of interest with DSD staff investigating their own peers.

Continued DSD Understaffing

Not including contracted or on-call workers, the DSD is authorized to employ 875 full-time uniformed personnel and 254 full-time civilians. Despite 2022 being named the DSD’s “Year of Retention” and the continued efforts of the DSD, DOS, and Mayor’s Office, DSD began 2022 with 636 uniformed personnel and 174 civilians and ended with 570 uniformed personnel and 177 civilians.40 This has resulted in mandatory overtime for all uniformed employees, and it is not uncommon for deputies to work 14 – 16- hour shifts.

Adequate staffing is of particular concern to the Board as it has a direct impact on the quality of life and mental health of both inmates and Sheriff deputies. The impact to inmates includes the amount of time they are allowed to be outside their cells (“out time”), the frequency they may shower, and the extent of programming available to them (such as continuing education, job training, and recovery programs). Long shifts and extensive overtime work can also degrade the mental health of deputies. Relevant research shows that long work hours have the potential to threaten not just officer decision-making and performance, but also their health and safety.41 The Board is also concerned about the potential for more use of force incidents when deputies may lack the emotional capacity or energy to safely de- escalate high-stress situations. The Board asked Sheriff Diggins to look into the available data to see if it supports the Board’s concerns.

In a November 2022 meeting with the Board, Sheriff Diggins outlined his four-part plan to address recruitment and retention. It includes weekly and monthly minimums for overtime work to spread out the work and provide additional scheduling predictability, salary increases and bonuses, morale boosting activities, and expedited training programs for individuals with prior experience working for the DSD or in other correctional facilities.

The Board believes that Sheriff Diggins is taking the staffing challenge seriously. We support his efforts to improve DSD staffing levels and eventually eliminate the need for mandatory overtime work. Nevertheless, we emphasize that additional and sustained attention to this issue is required.

LoDo Shooting

On July 17th, 2022, during the early morning “out crowd” that occurs when downtown bars close, three DPD officers attempted to stop Jordan Waddy. Waddy had previously been involved in an altercation and had a handgun in his hoodie pocket. As he removed and discarded his handgun, three officers fired at least 7 bullets at him. As a result, Waddy and six other bystanders were injured.

In the week after the shooting, the DPD provided a briefing on the case. A month after the incident, the body camera footage was publicly released. The Board did not have access to any of the footage prior to its public release. The OIM was allowed to view parts of the footage on two occasions, but similarly lacked direct or independent access that would facilitate close review. As a result, the COB’s ability to verify the DPD’s narrative of the incident was limited, particularly as it related to Waddy’s handling of his gun before the officers fired their weapons.

Relatedly, of the body camera footage shared publicly, only one officer activated their body worn camera prior to the shooting. At the time of this incident, DPD’s body cameras kept a rolling 30 seconds of video footage in a buffer recording, which is saved when the camera is activated. However, the cameras did not capture audio in their buffer recordings, and available audio from the one officer begins only 3 seconds prior to the shooting, limiting our understanding of the context and any orders or instructions the officers may have given prior to firing their weapons.

On December 16, 2022, EDOS Saldate informed the Board that he is in the process of approving a policy change requiring that footage of critical incidents be promptly and consistently uploaded into the IAPro database. The Board is grateful to EDOS Saldate for his openness to this policy change and hopes to see this issue resolved in 2023.

Police Use of Force Review Boards

The DPD’s Use of Force Review Board is responsible for reviewing all officer uses of force that involve death, serious bodily injury, or officers discharging their firearm.42 The Board is composed of 5 voting members: 2 DPD Commanders (Major Crimes + Rotation), 2 Denver community members, and 1 member from another Colorado law enforcement agency. The DPD selects and trains the community member participants, and the Chief of Police selects the partnering law enforcement agency.

The OIM attends all of the Review Board’s meetings and can typically provide comments and ask questions but does not have a defined role in the proceedings.

The DPD’s Use of Force Review Board’s proceedings are protected by the privilege of deliberative process.43 As a result, the COB is very limited in the details that it can publicly report about the Review Board’s operations.

However, there are fundamental aspects of this body that the COB has concerns about, particularly given the importance of reviewing use of force incidents by the DPD. At its most basic level, the Review Board is neither transparent nor independent. All of its members are either employed by or hand-picked by the DPD, the names of its members are not public, and all of its proceedings are shielded from disclosure by the DPD’s deliberative process privilege.

Then-Mayor John Hickenlooper added community participants to the DPD’s Use of Force Review Board around the same time that the COB and OIM were created.44 If his intention was to improve the Use of Force Review Board’s transparency, increase its legitimacy, or ensure that a meaningful variety of perspectives are represented, it did not. It is the position of the COB that trust in the review and discipline process is earned through transparency and meaningful engagement with diverse views.

Recommendations

City ordinance empowers and requires the Board to make and publish recommendations for how Denver’s public safety agencies can both improve their relationships with the public and improve their policies or rules related to the hiring, training, or complaint processes. Additionally, Denver’s Charter empowers the Board to “address any other issues of concern to the community.”

2022 Recommendations – Based on the Board’s work in 2022, it makes the following recommendations:

DPD:

Use of Force Review Board: The DPD should critically evaluate the current purpose and value of their Use of Force Review Board and whether structural changes would help it better accomplish its goals. Currently the Review Board is neither transparent nor independent. This Board offers the following recommendations for specific changes to the community participation aspect of the Board:

- Allow open applications for community members who want to serve on the Review Board.

- Establish a clear rotation and term limits for community members who participate on the Review Board.

- Publish additional information about the Review Board, its membership, its meetings, how community members can apply to join the membership pool, and the selection process.

DPD Community Engagement: The DPD should work to better publicize existing opportunities for the community to engage with their local districts and police leadership. There is currently no central hub or public source for community members to learn about meeting times and locations to interact with DPD districts and leadership.

DSD

DSD Staffing: The DSD should continue to make every effort to increase recruitment and retention rates among both uniformed and civilian personnel.

- City agencies should seek out ways to partner with the DSD in promoting their recruitment efforts.

- The DSD should continue to make every effort to appropriately compensate staff for the important work that they do.

- The DSD should continue to improve non-financial retention factors such as workplace culture and employee wellness programs.

Oversight of Medical Staff: The DSD should ensure that they exercise sufficient oversight over the performance of Denver Health’s staff and the process by which complaints related to medical staff and services are handled.

- The DSD should require Denver Health to provide it with written summaries of how complaints against Denver Health staff are addressed and resolved. If the DSD is not satisfied by how the complaint was addressed, the DSD should contractually reserve the right to conduct additional investigative work with the full cooperation of Denver Health staff.

- The DSD should publish aggregated data about complaints related to medical care and their outcomes on an at least annual basis.

- The scope of administrative investigations into in-custody deaths should be expanded to include the conduct of any contract personnel involved. Any contractual barriers to this should be identified and eliminated.

Appendix A

| Strategic Goals | Objectives | Activities | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate Funding and Operational Resources | – Hire and supervise new monitor– Increase monitor and staff salaries, staffing, andbandwidth for effective oversight– Make board membership more accessible tocommunity members– Amend board bylaws– Clarify roles and standardize training for boardmembers | – Request salary study for monitor position– Write performance plan for monitor position– Assist Monitor in setting strategic direction of OIM– Develop board member role description, interest packet, onboarding checklist, orientation, ongoing training, offboarding, and exit interview– Amend board bylaws– Shorten nominating process for board members | Salary StudiesVacancy Rates |

| Sustained Stakeholder Support: Community Outreach and Involvement | – Engage and catalyze community to raise visibility of Citizen– Oversight Board and Office of the Independent Monitor, prioritizing strong, open relationships and working together to reform the oversight system– Publish more resources for the public– Prepare for new mayor and council members in 2023 | – Prepare community engagement plan with calendar of events– Participate in community-hosted events– Publish and update web page with history of the Citizen Oversight Board and Office of the Independent Monitor– Educate political candidates about roles of Citizen Oversight Board and Office of the Independent Monitor | Participation at EventsPublic Awareness |

| Unfettered Access to Records and Facilities; Public Reporting and Transparency | – Issue more data analysis, reports, and recommendations than in previous years– Develop an approach to enable the OIM to drop-in on public safety departments – Increase independence and transparency of use of force review boards at DPD– Enhance transparency of process governing misconduct and policy complaints– Enhance oversight and transparency of Denver Health’s performance in providing medical care to incarcerated persons | – Pursue outstanding data requests to agencies– Develop strategy, templates, and checklists for reports and public statements– Develop research priorities and partnerships– Develop research strategy for drop-ins, use of force review, and misconduct and policy complaints– Monitor implementation of public portal for IAPro database– Analyze Denver Health contract with DSDData requests and CORA requests | Reporting Implementation |

Appendix B: Board Membership

Julia Richman, Chair

Currently serves as the Deputy Executive Director of the Governor’s Office of Information Technology (OIT), overseeing a broad scope of agency operations and key strategic initiatives. She joined OIT as the Chief Strategy Officer in 2020. Previously, Julia was the Chief Innovation and Technology Officer for the City of Boulder and a Senior Manager with Deloitte Consulting. Richman was born and raised in Colorado’s metro area. She is a Colorado Governor’s Fellow, and a graduate of Leadership Denver. She also sits on the boards for the Colfax Marathon and her Registered Neighborhood Organization (RNO). She received her MPP from the University of Chicago and AB from Dartmouth College.

Nick Webber, Vice Chair

Is a supervising attorney at the Denver Trial Office of the Colorado State Public Defender, where he has worked since 2014. As a Deputy Public Defender, Nicholas works to protect the constitutional rights, liberties and dignity of indigent people accused of committing crimes. Nicholas has worked on all types of cases in his tenure at the public defender’s office, from misdemeanor traffic offenses to homicides and violent crimes. Nicholas is a Denver native, but left Colorado to obtain his bachelor’s degree from Boston University. After college, he worked with low-income families at a Jesuit school in Ecuador before earning his law degree from Santa Clara University. Prior to becoming a public defender, Nicholas worked at the Watsonville Law Center Legal Aid Clinic in California, as an Equal Justice Works Fellow advocating for migrant worker rights. He also interned with the Santa Cruz California Public Defender’s Office and served as a board member for the Pajaro Valley Women’s Shelter.

Terrance D. Carroll

Was the 54th Speaker of the Colorado House of Representatives. He is the only African American to have served as Speaker of the Colorado House. Terrance served in the legislature from 2003 until being term-limited 2011. Terrance has been listed by 5280 Magazine as one of the “50 Most Influential People in Denver.” Terrance’s entry noted his reputation as a skillful dealmaker, stating that he is a “critical and respected negotiator.” Terrance is a Senior Voting and Democracy Fellow with FairVote and a former police officer. He is a graduate of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law, and holds a Master of Divinity degree from the Iliff School of Theology in Denver.

Karen Collier

Retired from public service in 2009, having worked in the Denver District Court as a court stenographer for 32 years. Since then, she has worked as an Alpine Ski Instructor in Winter Park and Granby, instructing differently-abled and abled-bodied youth and adults in Alpine skiing and as a tennis instructor with Denver Citywide Sports. In addition to the appointment to the Citizens Oversight Board, she sits on the Board of The Center for Trauma and Resilience and is a co-chair of Park Hill Congregational UCC’s partnership with the Women’s Homelessness Initiative, a program of the Capital Hill United Ministries, providing daily shelter to women who are homeless in Colorado.